Just after the dawn of the 20th century, when Calgary was small western city of a few thousand people and dusty roads, a group of women decided their rough-and-tumble community needed some sophistication. So they set about to create something to signal that the prairie community had some culture.

With determination and grit, they secured $80,000 from a U.S. philanthropist and went door-to-door, convincing local ranchers and farmers to sign petitions. And, they got a library built. It was to be the first public library in Alberta. It still stands today in the heart of Calgary: the Memorial Park Library.

‘Woman with a dream’

Many of these women were well-read and educated, having come from metropolitan centres in the East to make a life on the frontier with their enterprising husbands in the growing western city. They were the wives of professors and politicians, but the women themselves are remembered in historical records only as the Mrs. to their notable husbands. It is no small irony the names of the women who helped create a lasting Calgary institution are nearly lost to history.

But these women changed the face of the city.

Memorial Park Library, pictured here sometime between 1930 and 1937, was the first public library in Alberta.(Reeves/Glenbow Archives)

One of them we do know well: Annie Davidson, who lead the campaign. The public library was her brainchild.

“What’s really beautiful about it is, it’s just one woman with a dream, a woman who’s been through all kinds of hardship but is really determined to build a better place — and she succeeded,” says Rosemary Griebel, reader services director for Calgary Public Libraries.

‘Diehards’ of reading

Sometime in her late 60s, New Brunswick-born Davidson arrived in Calgary from Manitoba with a trunk full of books. She was a widow and wanted to live closer to her remaining children. She’d had 10, but six of her children had died of illness or accident.

Davidson found solace in reading classics and the Bible. Her passion for books became a tool to make friends.

And so, in 1906, at the age of 68, Davidson started the Calgary Women’s Literary Club. Each week the women met in the parlour at Davidson’s house at 13 Avenue West.

“They read intense stuff. This wasn’t murder mysteries, it wasn’t Agatha Christie. They were reading like crazy politically-based novels if not political books,” says Barb Worth, who has researched the club.

“And they would talk about them in depth. These women were diehards.”

Annie Davidson was 68 when she started the Calgary Women’s Literary Club and petitioned for the first public library in Calgary. (Calgary Women’s Literary Club)

Many of the women were recent arrivals to Calgary and surrounding farms. They were married and trying to adjust to life in a community of about 12,000 souls. One member of the reading club described the shared literary discussion as a means to escape from “small worries.”

“Many women led humdrum lives out of necessity,” a Mrs. Jacobs wrote in the club’s archival materials. “[They] live far out in the country and … depend on reading to get those things they are unable to obtain otherwise, such as adventure, travel and romance.”

This club, with its members’ wish for adventure, would lead to an intellectual revolution of sorts. Davidson decided the broader community needed a library, one that people of all social standing could enjoy.

Persistent petitioners

Davidson contacted a philanthropist in the United States, Andrew Carnegie, who had started donating thousands to build free public libraries across North America: the famed Carnegie Libraries. She secured a promise of $80,000 — a small fortune — toward the building of the library, if the local community would pitch in a few dollars as well.

Calgary’s all-male council, however, said they would lend their support only if Davidson submitted a petition with signatures from 10 per cent of Calgary men. The women, at that time, weren’t allowed to vote.

Calgarian Ethel Baker is pictured outside the Memorial Park Library in 1940. (Glenbow Archives)

Davidson and her group set out to knock on doors and then went knocking again. It took two tries but the group eventually did get the hundreds of signatures required.

“They believed in knowledge for all so they were very committed,” Worth says. “They wanted that built and they wanted a space for women.”

“I can only imagine, she must have been very persuasive, as were the other women that were with her,” says Mary Carwardine, a member of the modern-day Calgary Women’s Literary Club. “These women were determined.”

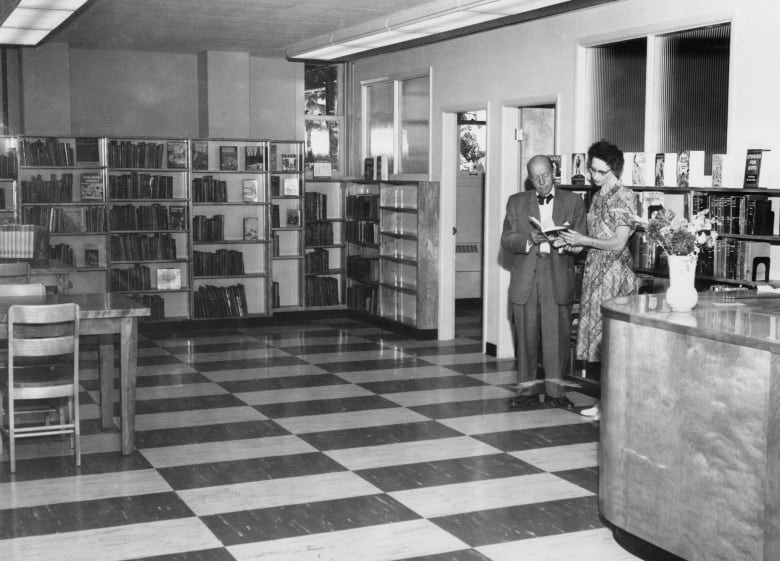

William Castell, director of the Calgary Public Library, and Dorothy Rogers, head of children’s department, open a new boys and girls section in 1959 at Memorial Park Library. (Ron Meigh/Calgary Herald/Glenbow Archives)

Carwardine is one of the few people who’ve tracked down the club’s history. This week, she and others celebrated their work at a plaque unveiling to mark the Memorial Park Library becoming a federal historically designated site.

The plaque details the work of Davidson and the Calgary Women’s Literary Club to bring the library to Calgary.

The new plaque, which marks the historical significance of the library, details the story behind how the library was brought to Calgary by Annie Davidson and the Calgary Women’s Literary Club. (CBC)

Library to ‘live on for generations’

Memorial Park Library opened in 1912 as a two-storey sandstone building in Central Memorial Park. It held 5,000 books.

Designed by Boston architectural firm McLean & Wright, it mirrored other Carnegie libraries with its pillars, stone stairs and curved facade.

“I’m so proud of it. I’m so proud that we have that great site, which was founded by one determined woman, and to know that it’s going to live on for generations,” Griebel says.

Stonemason James Carr replaces damaged stones as part of the restoration of Memorial Park Library in 1977. (Marla Strong/Calgary Herald/Glenbow Archives)

Davidson never saw the library herself. She moved to Montreal before it opened and died shortly afterward.

Her revolutionary work continued, however. Its first librarian, Alexander Calhoun, picked up her mantle.

As a scrappy visionary, Calhoun started children’s programming, training librarians to focus on youth despite libraries traditionally being for adults.

Chief librarian Alexander Calhoun, front right, stands with a group in front of the newly opened Memorial Park Library in approximately 1912. The building was recently designated a national historic site. (Glenbow Photo Archives)

Calhoun launched free adult classes in humanities and social sciences, in keeping with his socialist preferences. When the Great Depression hit, the library was so popular, they had to limit the number of books each person could check out to make sure some remained on the shelves.

Today, Calgary has 20 library branches. Later this fall, Calgary Public Libraries will open a huge new downtown library — already lauded for its architecture and value as a soon-to-be community hub.

Those are clear signs Davidson’s belief — that literacy can make a city — lives on, Griebel says.

“Every day I’m witness to how it improves lives, how it changes lives,” she says. “So I’m with Annie on that. I think we’re a very, very fortunate city to have access to such great libraries.”

View the article online by Rachel Ward for CBC News